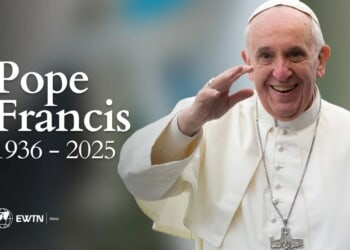

Vatican City, Apr 21, 2025 /

09:00 am

Pope Francis’ death today marks the end of a historic 12-year papacy. The first Latin American and the first member of the Society of Jesus to be elected pope, his legacy will be shaped by his efforts to bring the Gospel to the peripheries of the world and the margins of society while shaking up — sometimes vigorously and uncomfortably — what he saw as an unacceptably self-referential, unwelcoming, and rigid Catholic status quo.

After Pope Benedict XVI’s unexpected resignation in February 2013, Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Buenos Aires was given a mandate for reform on March 13, 2013, by the cardinals in the conclave convened.

Ahead of the 2013 conclave, the 76-year-old Jesuit from Argentina was not initially considered a front-runner. However, after he presented his vision for Church reform in a speech to the cardinals leading up to the conclave, a majority of electors were persuaded that he would offer a strong response to the ongoing scandals and challenges roiling the Church and provide solutions to collapsing Church attendance and vocations.

Taking the name of the 13th-century Italian saint and founder of the Franciscan order, Francis of Assisi, who adopted a life of radical poverty as he served those in need and preached the Gospel in the streets, the new pope aimed at fostering a Church reaching out to the poor, marginalized, and forgotten and capable of dealing with the complexities of the faith and human relationships in the world today.

“I prefer a Church which is bruised, hurting, and dirty because it has been out on the streets rather than a Church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security,” Francis stated in Evangelii Gaudium (“The Joy of the Gospel”), his 2013 apostolic exhortation that called for pastoral engagement in slums and boardrooms.

Evangelii Gaudium was considered a manifesto for the new pontificate. Still, the true blueprint for his pontificate predated his election and was distinctly Latin American: the 2007 concluding document of the Fifth General Conference of the Latin American episcopate held in Aparecida, Brazil, that Cardinal Bergoglio was chiefly responsible for drafting.

The “Aparecida Document” introduced many of the strategies for evangelization later taken up in Evangelii Gaudium and reiterated in Querida Amazonia, his 2020 postsynodal apostolic exhortation written in response to the 2019 Synod of Bishops for the Pan-Amazon region.

Aparecida called for a “great continental mission,” an outward-looking, humble Church with a preferential concern for creation, popular piety, the poor, and those on the peripheries. “It will be,” he wrote, “a new Pentecost that impels us to go, in a special way, in search of the fallen away Catholics, and of those who know little or nothing about Jesus Christ, so that we may joyfully form the community of love of God our Father. A mission that must reach everyone, be permanent and profound.”

Once pope, Francis made the “great continental mission” an undertaking for the universal Church.

Speaking in 2013 at World Youth Day in Rio de Janeiro, he urged his youthful audience to be unafraid of shaking things up in order to evangelize more effectively.

“What is it that I expect as a consequence of World Youth Day?” he asked them. “I want a mess. … I want to get rid of clericalism, the mundane, this closing ourselves off within ourselves, in our parishes, schools, or structures. Because these need to get out!”

In pursuit of this “messy” evangelization, Francis offered a grand vision of decentralization, listening, and accompaniment, a Church of pastoral and merciful engagement over rigid doctrinal precision and clericalism. The pope frequently declared “Todos, todos, todos” (“All, all, all”) as an expression of how the Church must be a welcoming place of mercy.

In December 2015, Pope Francis inaugurated an extraordinary Jubilee Year of Mercy, a special time for the Church to help the whole Church “rediscover and make fruitful the mercy of God, with which all of us are called to give consolation to every man and woman of our time.” Missionaries of Mercy were commissioned in 2016 to preach the gospel of mercy and make that invitation concrete through the sacrament of confession.

The centerpiece of his final years was the ongoing pursuit of synodality for the Church embodied in the three-year Synod on Synodality (2021–2024), aimed at permanently recasting the global Church so that all its members, the people of God, “journey together, gather in assembly, and take an active part in her evangelizing mission.”

(Story continues below)

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Yet from early on, his pontificate brought to the surface existing tensions within the Church, beginning at the tumultuous 2014 and 2015 Synods on Marriage and the Family, where cardinals debated the controversial proposal to lift the Church’s ban on reception of Communion for the divorced and civilly married. Francis’ postsynodal apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia (“The Joy of Love”) failed to dampen the controversy due to its unclear position on this contentious doctrinal issue.

These divisions deepened further in the years after as some Church leaders, particularly in Germany, seized on Francis’ seeming doctrinal ambiguity to press for changes to Church teachings such as priestly celibacy, homosexual unions, and women’s ordination. Tensions mounted further in the reaction across the Church to the 2021 decree Traditionis Custodes (“Guardians of Tradition”), which sharply curtailed the Traditional Latin Mass, and the 2023 decree Fiducia Supplicans (“The Supplicating Trust of the Faithful”) that permitted forms of nonliturgical blessings to same-sex couples and couples in irregular situations.

The Holy Father, however, drew clear lines in the sand on key teaching areas. With the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith’s 2024 document Dignitas Infinita (“Infinite Dignity”), Francis reaffirmed the Church’s perennial opposition to abortion, euthanasia, and gender ideology. He used a much-publicized CBS “60 Minutes” interview in May 2024 to state again categorically that women’s ordination to the priesthood and the diaconate was off the table.

By the end, he had disappointed Catholic progressives and many in the secular media who had expected a full-scale doctrinal revolution in the Church rather than the process of pastoral reform he pursued.

A child of immigrants

Born on Dec. 17, 1936, in Buenos Aires, Argentina, Jorge Mario Bergoglio was one of five children of Italian immigrants. His father, Mario, was an accountant for the country’s railways, and his mother, Regina Sivori, was a housewife.

Raised in the bustling lower-middle-class Flores sector in the center of Buenos Aires, young Jorge spent a good deal of time with his beloved grandmother, Rosa, whom he credits with introducing him to the faith.

However, the critical moment in discerning his vocation occurred on Sept. 21, 1953, when he experienced a life-changing encounter with God’s mercy in the confessional. “After making my confession I felt something had changed. I was not the same,” he recalled in 2010. “I had heard something like a voice, or a call. I was convinced that I should become a priest.”

After completing studies to become a chemical technician, he entered a diocesan seminary. He transferred to the Jesuit novitiate in 1958, was ordained a priest in 1969, and made his final profession with the Jesuits in 1973.

In short order, he served in various roles with increasing levels of responsibility. He became provincial of the Jesuits in Argentina in the same year as his final profession, when he was just 36 years old.

He held that office for six years, a period that overlapped with the turbulent aftermath of the Second Vatican Council that convulsed the Society of Jesus’ established practices and with Argentina’s infamous Dirty War (1976–1983), during which the military junta ruling the country tortured and “disappeared” tens of thousands of dissidents and political opponents.

The horrors of the Dirty War forged in the young Jesuit priest a deep and abiding antipathy for political ideologies, whether they originated on the left or the right.

And though some Jesuits in Latin and Central America would later embrace Marxist elements of liberation theology and revolutionary struggle, he and most of his Argentine brethren rejected that path.

The Argentinean “current” of liberation theology “never used Marxist categories, or the Marxist analysis of society,” Jesuit Father Juan Carlos Scannone explained in “Our Brother, Our Friend: Personal Recollections about the Man Who Became Pope.” “Bergolio’s pastoral work is understood in this context.”

Leading with controversies

While navigating the treacherous political landscape of the period, Father Bergoglio stirred enormous controversy as he undertook reforms of the local Jesuit province. By his own admission, much of the disagreement stemmed from his imperious leadership style at the time. “I had to deal with difficult situations, and I made my decisions abruptly and by myself,” he said in a 2013 interview. “My authoritarian and quick manner of making decisions led me to have serious problems and to be accused of being ultra-conservative.”

Following his time as provincial, he served from 1980–1986 as rector of the Jesuit seminary in San Miguel. His tenure as rector was again divisive, with critics accusing him of trying to reshape the institution along pre-Vatican II lines that conflicted with contemporary Jesuit practices elsewhere in Latin America.

“He was not, as some have accused him of being, a conservative who wanted to take them to the preconciliar era but a renewalist, like Benedict XVI, who resisted attempts to conform the Church to the world in the name of modernity,” papal biographer Austen Ivereigh told the National Catholic Register, CNA’s sister news partner, as he discussed Father Bergoglio’s estrangement from the local Jesuits and his subsequent “internal exile” from his religious order that endured until he was elected pope.

After leaving his seminary post, he traveled to Germany in 1986 with the goal of finishing his doctorate. After his return, he initially maintained a position of influence among the local Jesuits. But in 1990, now in his early 50s and with his critics also now in a position of dominance, Father Bergoglio was sent away from Buenos Aires to serve as the spiritual director and confessor of the Residencia Jesuita community in Córdoba, Argentina. It was a disciplinary move, undertaken with the approval of Father Peter-Hans Kolvenbach, the superior general of the Society of Jesus, that Francis recalled as “a time of great interior crisis” in a 2013 papal interview.

Still, Father Bergoglio’s no-frills austerity, closeness to the poor and prodigious capacity for humble hands-on service inspired a cadre of young Jesuit disciples to emulate his priestly gifts during and after his rocky tenure as provincial and seminary rector.

“When we would get up at 6:30 or 7 to go to Mass, Bergoglio would have already prayed and already washed the sheets and towels for 150 Jesuits in the laundry room,” recalled Jesuit Cardinal Ángel Rossi, a former student at the Residencia Jesuita community, in “Pope Francis, Our Brother, Our Friend: Personal Recollections about the Man Who Became Pope.”

Episcopal service

In 1992, at the request of Cardinal Antonio Quarracino of Buenos Aires, Pope John Paul II unexpectedly plucked Father Bergoglio from his exile in Córdoba by appointing him auxiliary bishop of Buenos Aires. In 1997, John Paul II named him coadjutor archbishop of Buenos Aires with the right of succession. Upon Quarracino’s death in February 1998, Bergoglio became the metropolitan archbishop of Buenos Aires. John Paul II elevated him to the College of Cardinals in 2001.

As archbishop, he famously eschewed the trappings of office, traveling on the subway, residing in a simple apartment, and devoting much of his time to the poor and those living in the city’s slums.

Meanwhile, he showed himself to be politically astute, unafraid to confront Argentina’s political leaders, and a practitioner of elements of Peronism — the “third way” nationalist platform of the late Argentine strongman Juan Peron, who celebrated Argentina’s Catholic roots and ramped up social spending while eschewing both Marxism and capitalism.

“Power is born of confidence, not with manipulation, intimidation, or with arrogance,” Cardinal Bergoglio said in a 2006 homily that took aim at Argentina’s Kirchner government, which had adopted a more left-wing approach to Peronism than his own position and had clashed with the archbishop on moral issues.

Beyond Argentina, his major role at the 2007 Fifth General Conference of the Latin American episcopate in Aparecida, Brazil, thrust him into greater prominence in the global Church. Writing in First Things in 2012 about the final document, Catholic commentator George Weigel highlighted its evangelical focus.

“The first thing to note about the Aparecida Document is its strongly evangelical thrust: Everyone in the Church, the bishops write, is baptized to be a ‘missionary disciple,’” Weigel said approvingly, in words that presciently anticipated Francis’ vision for the papacy. “Everywhere is mission territory, and everything in the Church must be mission-driven.”

A pontificate of the peripheries

Eight years after reportedly finishing as the runner-up in the 2005 conclave that elected Pope Benedict XVI, Cardinal Bergoglio was picked by the College of Cardinals to succeed the German-born pope. The newly elected pontiff — the first non-European pope since Gregory III in 741 — immediately set the tone for his pontificate. “You know that the duty of the conclave was to give a bishop to Rome,” he declared from the loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica on the evening of his election. “It seems that my brother cardinals went almost to the end of the world to get him. But here we are.”

Many of the concerns he pursued in Argentina and at Aparecida became foundations for his papacy. He shunned traditional papal garments and moved into the Domus Sanctae Marthae, the Vatican guesthouse, instead of the traditional papal apartments in the Apostolic Palace. He continually emphasized the need for a Church that “goes out of herself to evangelize,” searching out and accompanying those on the “peripheries” of human existence. Important maxims from the Francis pontificate — the Church as a field hospital, “going out to the margins,” and the need for Church leaders to “smell like the sheep” — were complemented by a series of powerful images, such as the Holy Father washing the feet of prisoners and a young Muslim on Holy Thursday, embracing a disfigured man in St. Peter’s Square, and posing for selfies with young people.

Francis repeatedly reemphasized the centrality of this evangelical approach. “The true Church is at the peripheries,” he stated in Disney’s documentary “The Pope: Answers,” released in April 2023.

His first trip outside Rome after his election was to the small Mediterranean Italian island of Lampedusa, where he drew attention to the plight of undocumented migrants crossing deadly seas to enter Europe. He often spoke of the terrible plight of migrants and refugees, the divide between the global north and south and between the developing and wealthy countries, warning against economic policies that exploit poorer nations, a reflection of his familiarity with capitalism from a Latin American perspective. He criticized sharply what he called a “globalization of indifference” — an attitude that ignores people’s suffering on the margins of society and a “throwaway culture” that viewed the weak and vulnerable as disposable.

One similar recurring feature of this focus on the peripheries was his framing of efforts by wealthy nations to impose abortion, contraception, and gender ideology on developing countries in return for aid and development as manifestations of “ideological colonization.”

Such condemnations demonstrated that Pope Francis’ outreaches to the margins of human society defied efforts to cast him as a supporter only of progressive political and social agendas. During his April 2023 visit to Hungary — a European nation whose conservative alignment supposedly conflicted with his papal priorities for that continent — he denounced “the baneful path taken by those forms of ‘ideological colonization’ that would cancel differences, as in the case of the so-called gender theory, or that would place before the reality of life reductive concepts of freedom, for example by vaunting as progress a senseless ‘right to abortion,’ which is always a tragic defeat.”

The Holy Father’s informal communication style — highlighted by interviews such as the ones he gave to the late Italian atheist journalist Eugenio Scalfari and his off-the-cuff comments, especially his press conferences on the papal plane — made possible the rise of a parallel, media-generated quasi-magisterium in which secular and progressive Catholic media used his comments to claim that he was calling for major changes to Church teaching.

One legacy-defining example occurred during an in-flight press conference on the way home from World Youth Day in Rio de Janeiro in 2013, when the Holy Father was asked to comment about a specific repentant Vatican official and the rumored existence of a gay lobby at the Vatican.

Francis offered a nuanced response to the query, distinguishing between a person simply being gay as opposed to participating in a lobby. “If someone is gay and is searching for the Lord and has good will, then who am I to judge?” he said. Instead of seeing it as a pastoral gesture toward homosexual persons, many news reports characterized the remark as a softening of the Church’s moral prohibition of same-sex acts, with no meaningful clarification provided afterward from the Vatican.

Pope Francis also sought to build bridges with the international community through his words and actions. The two encyclicals written entirely during his pontificate, Laudato Si’ (2015), on caring for our common home, and Fratelli Tutti (2020), which emphasized fraternity and social friendship, were well-received by the international press.

In total, Francis authored four encyclicals during his reign, complemented by seven apostolic exhortations and 75 motu proprio documents, making him one of the most prolific popes in terms of magisterial teaching.

His March 2020 urbi et orbi address and blessing, delivered amid the COVID-19 pandemic as he stood in an empty, rainy St. Peter’s Square, as well as playing the role of peacemaker by working to restore U.S.-Cuban diplomatic ties and offering to mediate an end to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, helped establish the pope as a spiritual father figure not only for the Church but also for the wider world. In 2024, he became the first pope to participate in the G7 meeting of world leaders, urging them to be aware of the threat and the promise of artificial intelligence.

The pope’s desire for negotiation and dialogue also led him to sign a secret agreement with Beijing on appointing bishops in 2018 — for which he received strong opposition. The agreement was slammed by human rights advocates and other critics as an “incredible betrayal” and “absolutely incomprehensible” as Beijing further clamped down on religious freedom and violated the agreement on numerous occasions. The Vatican did not back down, however, insisting that patience was needed for the initiative to bear fruit despite frequent violations of the accord by the Chinese communist regime and the increasingly draconian application of its program of “sinicization,” which mandates that all religions must conform to communist precepts and be independent of foreign influence.

Cardinal Marc Ouellet, head of the Dicastery for Bishops during much of Francis’ reign, said the late pope’s ability to generate interest in the Church from those on the outside was a sign of his “missionary style.”

“A missionary is at the borders; he is looking for those who are far away,” he told EWTN News in a February 2023 interview.

Pope Francis’ global missionary spirit was evident in his many papal travels. The late pope made 47 apostolic journeys outside Italy, visiting 61 total countries, averaging six countries per year. The rate was even higher than the five-per-year pace of the original “traveling pope,” St. John Paul II. Francis’ visits, which included places like war-torn Iraq, the Central African Republic, and South Sudan, indicated a preference for the Global South and nations plagued by conflict.

This preference for the global margins was further reflected in Pope Francis’ selection of many new members for the College of Cardinals. Through 10 consistories, he created 149 new cardinals, dramatically reshaping the college’s composition. During his pontificate, the makeup of the college underwent a historic transformation, falling from 52% European at the start of his papacy to just 35% today. The college now reflects a more global Church, with South America and Asia each representing 15% of cardinals, North America 17%, Africa 12%, and Oceania 7%.

Pope Francis was responsible for selecting 108 of the 135 cardinals who will now vote for his successor.

His global vision was particularly evident in his appointments of cardinals from countries with tiny Catholic populations, such as Mongolia and Morocco, from the peripheries, such as Tonga and Haiti, and from places of strife, such as Myanmar, South Sudan, and the Central African Republic.

Francis’ tendency to appoint members to the College of Cardinals based on personal instinct, recommendations, or connections over standing custom also led him to pass over candidates from long-standing cardinalatial sees. For instance, in the U.S., Archbishop José Gomez of Los Angeles, the former president of the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops and head of the largest archdiocese in the U.S., never received the red hat. At the same time, Pope Francis made Bishop Robert McElroy of the Diocese of San Diego a cardinal in 2022. Likewise, Archbishop Mario Delpini, a Francis appointee as head of the Milan Archdiocese, the largest in Italy, was also conspicuously deprived of the cardinalate.

But just as erroneous assumptions abounded about his supposed intent to abandon core points of Church teaching, there was also a mistaken belief that his appointments to the College of Cardinals were uniformly progressives. Many Francis appointees, such as McElroy, Cardinal Leonardo Steiner of Brazil, and the Jesuit Cardinal Jean-Claude Hollerich of Luxembourg, are committed progressives. At the same time, Francis named several known conservatives, including Cardinal Gerhard Müller, former prefect for the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith; Carmelite Cardinal Anders Arborelius of Sweden; and Capuchin Franciscan Cardinal Fridolin Ambongo Besungu of the Democratic Republic of Congo, who led the African bishops’ opposition to Fiducia Supplicans in 2024.

That balance in his appointments was similarly mirrored in the canonizations throughout his pontificate. Pope Francis canonized three of his predecessors, John XXIII, Paul VI, and John Paul II. He also canonized a total of 942 saints. These include the 813 Martyrs of Otranto; Salvadoran Archbishop Óscar Romero, a courageous critic of government human rights abuses; the great English convert and cardinal John Henry Newman; and Mother Teresa of Calcutta. The pontiff also added two new doctors of the Church: the Armenian St. Gregory of Narek and the Church Father St. Irenaeus of Lyon. He called Irenaeus the “doctor of unity.”

Internal reform

Francis’ outward emphasis was matched by serious efforts to reform the inner structures of the Catholic Church to free it up for a greater focus on mission and service. Early on, he appointed a council of cardinals to advise him on curial and Church reform. Its labors culminated in March 2022 with the promulgation of a new apostolic constitution for the Holy See, Praedicate Evangelium, that allowed dicasteries, or Vatican departments, to be headed by lay baptized Catholics and placed greater emphasis on evangelization. The Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples, which dates to 1622, and the Pontifical Council for Promoting the New Evangelization, created by Benedict XVI in 2010, were combined to form the Dicastery for Evangelization, presided over directly by the pope and superseding the long-standing position of preeminence of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith in the ranks of Vatican offices.

Francis tackled some aspects of Vatican finances, even as ongoing scandals overshadowed that progress. The pope himself was drawn into one high-profile fraud case that led to the trial and 2023 conviction of one of his closest cardinal collaborators, Cardinal Angelo Becciu, on allegations of financial misconduct.

Francis also undertook a series of reforms related to the scourge of clergy sexual abuse, beginning in 2014 with the creation of the Pontifical Commission for the Protection of Minors, headed by Cardinal Seán O’Malley of Boston, who was also a member of the pope’s Council of Cardinals. Francis convened a global Vatican summit on the issue in 2019, which gave rise to his new Vos Estis guidelines intended to strengthen provisions for bringing abusive priests to justice and holding bishops accountable for their handling of abuse allegations.

But the Holy Father’s style of governance — which often relied upon going with his gut instead of following established procedures and a tendency to keep all decision-making in his own hands — arguably led to blind spots in his crackdown on abuse.

“A handful of priests, bishops, and cardinals whom Francis has trusted over the years have turned out to be either accused of sexual misconduct or convicted of it, or of having covered it up,” AP Rome correspondent Nicole Winfield reported in 2020. This referred to Francis initially disbelieving allegations against a bishop in Chile that turned out to be true and also reportedly turning a blind eye to reports of former cardinal Theodore McCarrick’s sexual misconduct until allegations were made public in 2018. Questions were raised as well about Francis’ awareness of the case of the famed Slovenian Jesuit mosaic artist Marko Rupnik, who was accused of sexual misconduct, briefly excommunicated, and finally expelled from the Society of Jesus. At the end of the pontificate, the wider sex abuse scandal was still swirling in several countries, including Bolivia and Portugal.

Criticism of his handling of the abuse crisis reached a new level of severity in 2018 when Archbishop Carlo Maria Viganò, former nuncio to the United States, accused Pope Francis of negligence in handling allegations of sexual misconduct involving McCarrick and called on the pope to resign. By 2024, Viganò’s extreme rhetoric — including calling Francis a heretic — led to his condemnation as a schismatic by the Vatican.

Pope of synodality

One of Pope Francis’ most significant projects in the second half of his pontificate was his implementation of “synodality” in the life of the Church.

Reflecting the ecclesiastical vision that was articulated at Aparecida and in Evangelii Gaudium, Francis used the Synod of Bishops to craft a more listening Church, an “inverted pyramid” that took the people of God as its starting point and significantly raised the profile of the General Secretariat of the Synod under its secretary general, the Maltese Cardinal Mario Grech.

But many critics feared that his approach departed from St. Paul VI’s vision of a Synod of Bishops, could undermine Rome’s authority, lead to further confusion among the faithful, and open a path to change Church teaching in a host of areas.

Synods covering the family and marriage, youth, and the Amazon featured unfettered discussions, with some Church leaders openly demanding a change to Church discipline to address new pastoral realities on the ground, and even calling for granting women access to a form of the diaconate.

Francis’ 2016 postsynodal apostolic exhortation Amoris Laetitia (“The Joy of Love”), following from the sometimes contentious 2014 and 2015 Synods on the Family, made headlines for what critics saw as the creation of conditions in which the divorced and civilly remarried could receive Communion. Church leaders and dioceses offered dueling interpretations of the document’s pastoral guidance, and four cardinals’ September 2016 submission of five questions, or “dubia,” asking for clarity amid “grave disorientation and great confusion,” went unaddressed by the pope. Subsequent dubia sent to Rome in 2023 were answered by Francis’ new doctrine chief, Cardinal Victor Manuel Fernández, in terms that seemed to confirm the broadest interpretation possible.

Meanwhile, some radical lay German Catholics, with the support of most of the German bishops, found inspiration in the pope’s approach and launched their own Synodal Way to demand changes to Church teaching on priestly celibacy, homosexual unions, and women’s ordination. Despite being rebuked by Francis as “elitist,” “unhelpful,” and “ideological,” the Germans pushed ahead with their process and risked a schism.

At the same time, Francis faced disapproval from some conservative prelates who feared that his doctrinal ambiguity, his handling of the abuse crisis and his disparagement of some in the Church for clericalism and rigidity were confusing the faithful and demoralizing priests and seminarians.

Francis similarly created ripples with his treatment of Catholic communities attached to the Traditional Latin Mass. Traditionis Custodes, his 2021 decree restricting its celebration, shocked adherents to the rite and prompted even some of the pope’s liberal allies to characterize the document’s stern language and severe suppression as a stunning departure from the pope’s call for a synodal listening approach. Others, like the Dominican and longtime Vatican official Archbishop Augustine Di Noia, have argued that the pope’s intervention was necessary to head off the false idea that the pre-Vatican II Mass is the true liturgy for the true Church.

Immense controversy likewise surrounded the document issued by Fernández at the end of 2023, Fiducia Supplicans, that allowed nonliturgical blessings for same-sex couples and couples in irregular situations. The decree sparked strong disagreements among the world’s bishops, with almost all African bishops refusing to implement the decree, saying in a formal statement in January 2024 that “it has sown misconceptions and unrest in the minds of many lay faithful, consecrated persons, and even pastors.”

Francis, however, also was consistently clear on key areas of Church teaching. Through the 2024 decree Dignitas Infinita (“Infinite Dignity”) issued by the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, for example, Francis reiterated the Church’s perennial teachings on the dignity of the human person.

Undeterred by the critics, the Holy Father pushed ahead with his vision for a synodal Church launching in 2021 a multiyear, global consultative process, which ended in two “Synods on Synodality” in Rome in October 2023 and October 2024.

Francis made the unprecedented decision to forgo writing a postsynodal apostolic exhortation at the conclusion, choosing instead to directly implement the synod’s final document. “What we have approved in the document is enough,” he declared, marking a historic shift in how synodal reforms may be implemented.

Francis clearly intended to place the Church on a path from which, institutionally and even theologically, it would be difficult to turn back. This was especially apparent in his choice in 2023 of his friend, then-Archbishop Fernández, an Argentinian theologian and ghostwriter of several of Francis’ major writings, including Laudato Si’ and especially Amoris Laetitia, to be the new prefect of the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith and a member of the College of Cardinals. In the letter accompanying his appointment, Francis called on his new prefect “to verify that the documents of your own dicastery and of the others have an adequate theological support, are coherent with the rich humus of the perennial teaching of the Church and at the same time take into account the recent magisterium,” meaning Francis’ writings over the last decade, many of which Fernández himself helped write.

‘With doors always wide open’

Pope Francis’ health declined in his last years due to several medical challenges, including sciatica, respiratory issues, ligament damage in his knees, and two bouts of intestinal surgeries. Mobility issues forced him to start using a wheelchair in 2022. Still, he remained impressively active almost to the very end, maintaining a demanding schedule of audiences and travel, even while moderating his pace in his final months.

Many around the world will retain vivid images of Francis embracing the poorest and most stricken, a champion of mercy and accompaniment. He declared on the night of his election that he had come from the ends of the earth. In his unexpected and often unappreciated pontificate, he reached out to the ends of the earth to declare a place of welcome for all, “todos, todos, todos.”

“The Church is called to be the house of the Father,” he wrote in Evangelii Gaudium, “with doors always wide open. One concrete sign of such openness is that our church doors should always be open, so that if someone, moved by the Spirit, comes there looking for God, he or she will not find a closed door.”

On Dec. 24, 2024, as the first “pilgrim of hope,” he opened the Holy Door of St. Peter’s Basilica, inaugurating the 2025 Jubilee Year. In a historic first, he also opened a Holy Door within Rome’s Rebibbia prison, demonstrating his continued commitment to those on society’s margins.

The pontiff’s final medical challenge was a bout of pneumonia that led to a lengthy hospitalization in early 2025 from which he ultimately never recovered. His last public appearance was on Easter Sunday, where he took part in the traditional urbi et orbi. He struggled to be close to the Church and its people until the end, pushing to be present to the world in his frailty.

Pope Francis died on Easter Monday, April 21, in his apartment at Casa Santa Marta.

The pope’s death leaves the massive project of synodality and the curial reforms unfinished. It now falls to the cardinals to choose a successor who will decide how or whether to carry the Francis agenda forward. He bequeaths a polarized Catholic community beset by the crises of modernity and relativism. Still, his vision for a Church of the peripheries that listens and walks with the suffering with mercy unquestionably disrupted the status quo and launched a process that will continue to impact global Catholicism long after he is laid to rest.