Is the Office for Budget Responsibility too powerful? It is not. Influential it may be, but it has no power at all. But it suits politicians to say it does, just as it suits other politicians to rail against the Human Rights Act without acknowledging that a government can simply pass laws that contravene it so long as they’re prepared to say that’s what they’re doing, and they weren’t.

Excuses are comfortable, and it better flatters the politician – especially one who has served in government – to imagine themselves prisoners of a machine than merely unwilling to, or incapable of, operating it.

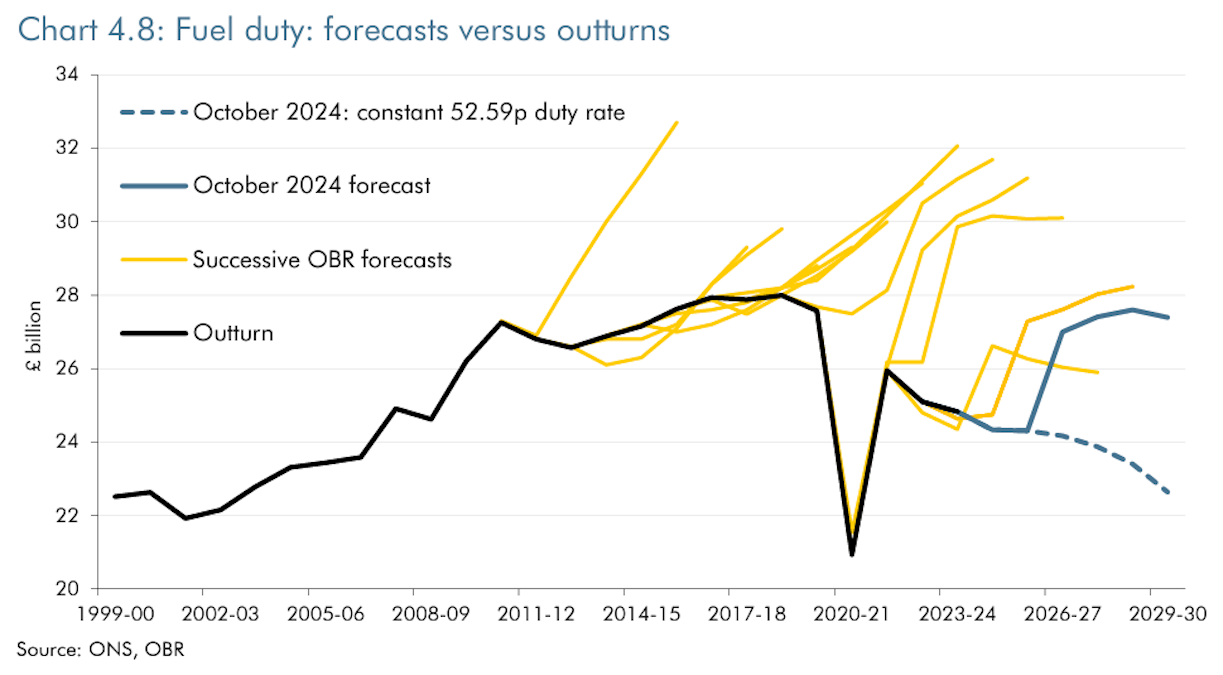

We’ll look more closely at the nature of the OBR’s ‘power’ in a moment. But first, let’s do some Data Journalism and illustrate the limits of it with a couple of charts. Here’s one you might recognise from our piece on Fuel Duty back in December:

Look upon its work, ye mighty, and despair!

Whatever terrible power the OBR possesses, it doesn’t extend to forcing any one of six successive governments to raise a relatively trivial tax. Including this one! In “good news for millions of drivers“, Rachel Reeves has chosen to once again extend the Fuel Duty freeze, putting the revenue on that sad-looking dashed line up there and blowing a £4bn black hole in her own accounting.

The OBR knew this, too. As we pointed out last time, it:

“…has done everything it can – within its official constraints – to signal its disbelief in its own forecast:

“In practice, these policies have rarely been implemented and the new Government is now continuing this practice. The reversal of the 5p cut has now been delayed three times and fuel duty has not been uprated with RPI since 2011.” (EFO Oct 24, s.4.26)

“This acidity isn’t tucked away; it is run through the document’s coverage of fuel duty like a stick of rock. The EFO refers to indexation as “seldom-implemented” in three separate places, and the 2022 cut is one of several ‘temporary’ policies where the temporary is in scare quotes.”

Yet despite this clear foreknowledge, the Chancellor somehow managed to enact – or in this case, not enact – her preferred policy anyway.

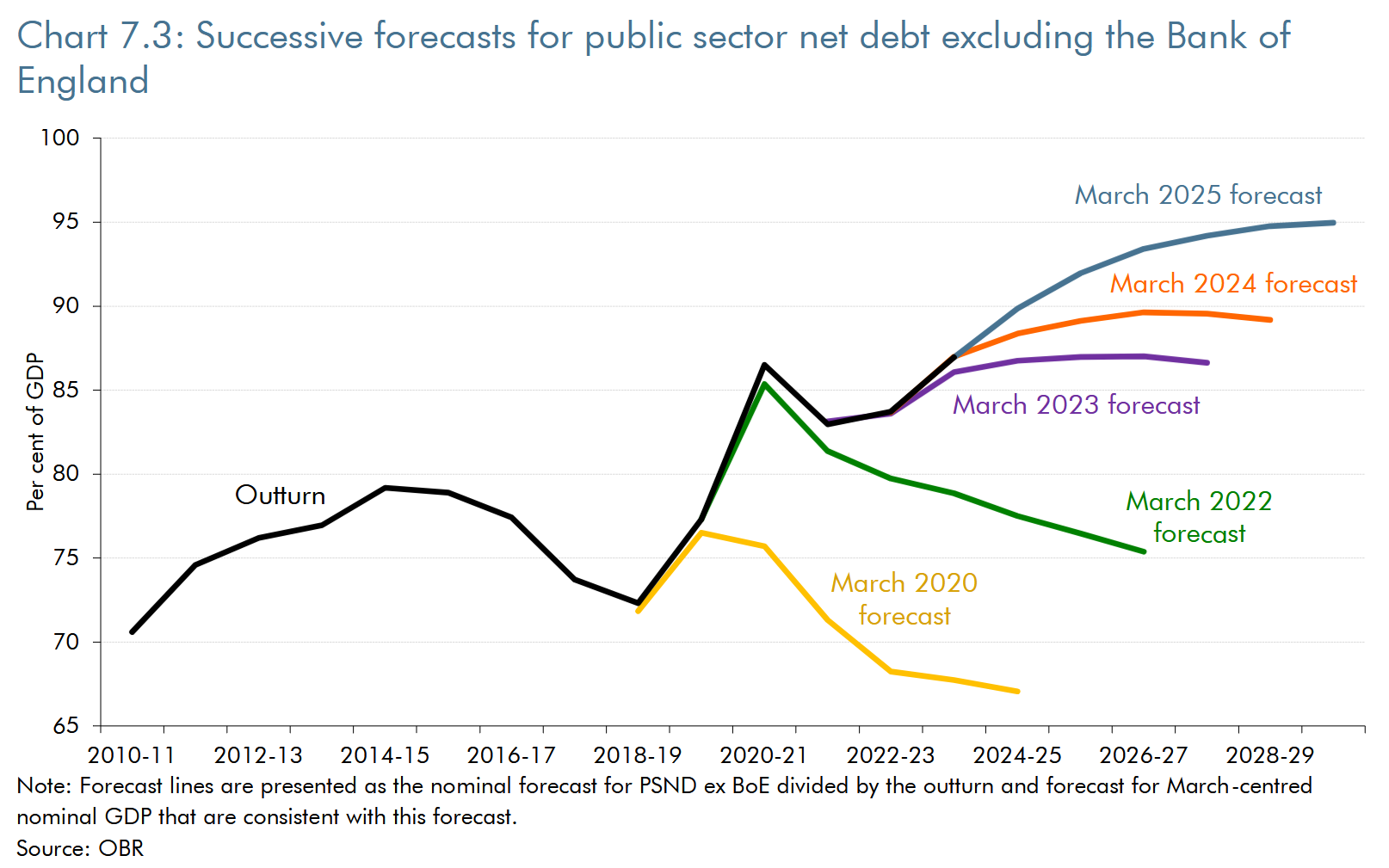

All right, but that’s a small policy in the grand scheme of things. What about the really big stuff? What about, say, the national debt? Well, here’s a chart from the latest EFO, released yesterday:

Pictured: the gentle upward gradient of responsible debt management.

The last chart proved you could get away with anything if you were prepared to lie to the OBR. This one suggests you don’t even need to lie to it. The Government officially has no plans to lower the national debt. Yet somehow, the great straitjacket of the nation’s fiscal hopes and dreams has failed again.

At root, the OBR has no more ‘power’ than do your bathroom scales. Neither can issue commands, but consulting either on a regular basis has a strong tendency to influence your behaviour.

To the extent that the OBR does end up fouling ministers, it is very often because they lie to it and themselves. It is legally obliged to take the government at its word; if you continually tell it you will raise Fuel Duty the day after tomorrow, you will continually need to make fresh cuts when you don’t.

Other times, they programme it to punch them in the face – by, for example, changing the fiscal rules to let themselves borrow more (another freedom the OBR, in its beneficience, continues to grant the chancellor) whilst leaving unchanged the rules on the current balance which mean debt interest still counts against the targets on the old terms.

On still other occasions, politicians will, despite continually grumbling that the OBR’s forecasts are often wrong, draw up their spending plans as if they were not. As one analyst put it to me: “When the OBR tells you for no reason that productivity will hit two per cent in 18 months time, don’t believe it and don’t spend the money.”

Are some its forecasts sometimes wrong? Yes indeed. But what is the basis for assuming this latter fact would afford more leniency to politicians? Forecasts can be wrong in either direction.

Does it sometimes refuse to accept the Treasury’s projected figures for growth policies? Yes, but preventing the Treasury from just making up its own numbers is the OBR’s entire job. Is the veneration that excuse-making politicians afford, or pretend to afford, the it hugely problematic? Yes! But now we’re aiming at a different, more deserving target.

The ministerial reflex to use it as a crutch is reason enough for reform. How politicians, the press, and the public treat an institution is profoundly important, whatever its ‘actual’ character. George Osborne did invent it, after all, with precisely the aim of constricting the chancellor’s de facto room of manoeuvre.

I recently made a similar argument for Policy Exchange about the Ministerial Code: the case for melting down the Golden Calf hinges not on the idol, but those dancing round it.

So there isn’t a case for overhauling how the OBR works – perhaps along the lines recently outlined Daniel Susskind, to more closely resemble other countries’ equivalents, which “simply assess the official government forecast or provide an alternative to sit alongside it”. Or smaller tweaks such as, say, don’t ask it to publish two EFOs a year if you only want to have one fiscal event.

But don’t let any politician get away with the idea that the iron grip of the OBR is anything other than feigned, or at best learned, helplessness. A majority in the Commons can do whatever it likes, and neither court no quango can gainsay it. If it appears otherwise, it is only because successive governments have built themselves a theatre of excuse-making and then, perhaps, forgotten its fake.

![Comedian Bill Burr Clings to Debunked Hoax About Elon’s ‘Nazi Salute’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Comedian-Bill-Burr-Clings-to-Debunked-Hoax-About-Elons-‘Nazi-350x250.jpg)