Voices of the Fallen Heroes and Other Stories

By Yukio Mishima

(Vintage International, 272 pages, $16)

There has always been reason to fear

The vengeful rage of angry ghosts.

— The Tale of the Heike

September 9, 1944. It is graduation day at Tokyo’s prestigious Gakushūin High School, and a senior by the name of Kimitake Hiraoka has come out at the top of his class. What is more, Hiraoka’s contributions to the Gakushūin literary magazine Hojinkai-zasshi, written under the pen name Yukio Mishima, have already earned him considerable renown, with the scholar and Shinto fundamentalist Zenmei Hasuda describing the literary prodigy as “a heaven-sent child of eternal Japanese history.”

To cause us human beings to pray to something within ourselves, to have faith in something within ourselves. Our deaths embodied that.

After the graduation ceremony is over, Mishima (as we shall henceforth refer to him) is whisked off to the imperial palace complex in a limousine, where he is awarded a gindokei, a commemorative silver watch, by Emperor Hirohito himself. Twenty-five years later, Mishima will still cherish this memory. “I watched the Emperor sitting there without moving for three hours. This was at my graduation ceremony. I received a watch from him,” he would relate during a 1969 debate with leftwing students at Tokyo University. “My personal experience was that the image of the Emperor is fundamental. I cannot set this aside. The Emperor is the absolute.”

February 10, 1945. Having received a draft notice the previous spring and then (barely) passing his initial conscription examination, Yukio Mishima presents himself for his mandatory pre-enlistment medical check-up. He is suffering from a cold, his face is pallid, his cheeks gaunt, his limbs thin and weak. The young army doctor in charge of his examination misdiagnoses him — inadvertently or intentionally, we cannot know — with pulmonary tuberculosis and declares him unfit for military service.

This comes as a shock to Mishima, who had spent the previous night clipping his hair and nails to serve as family mementos and writing a farewell letter to his family that ends with the words Tennō heika banzai, or “Long live the emperor.” His parents breathe a sigh of relief when they hear the news of his failed physical examination. Mishima is not so grateful and ponders whether he might still be able to join the Shinpū Tokubetsu Kōgekitai — the “Divine Wind Special Attack Unit” then undertaking suicide attacks against Allied naval vessels. He never does, but he will write in an April 21, 1945 letter to his friend Makoto Mitani that

It was through the kamikazes that “modern man” has finally been able to grasp the dawning of the “present day,” or perhaps better said, “our historical era” in a true sense, and for the first time the intellectual class, which until now had been the illegitimate child of modernity, became the legitimate heir of history. I believe that all of this is thanks to the kamikazes. This is the reason why the entire cultural class of Japan, and all people of culture around the world, should kneel before the kamikazes and offer up prayers of gratitude.

August 15, 1945. Like millions of his fellow Japanese citizens, Mishima has tuned his radio to NHK, whose newscasters had promised an announcement “of the highest importance.” The Kimigayo national anthem is played, the listeners at home are commanded to stand, and then Emperor Hirohito’s surrender broadcast, known officially as the Gyokuon-hōsō or the “Broadcast of the Emperor’s Voice,” is delivered.

Few commoners or even aristocrats have ever actually heard the emperor’s voice — Mishima, who met him less than a year ago, was a rare exception — and although the audio quality is poor, and Emperor Hirohito employs a courtly language so formal as to be almost impossible for the average person to understand, the thrust of the address is clear enough. “The enemy has begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb, the power of which to do damage is, indeed, incalculable, taking the toll of many innocent lives. Should we continue to fight, not only would it result in an ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation, but also it would lead to the total extinction of human civilization.”

Surrender is the only option, but Japan will survive, if the people “continue as one family from generation to generation, ever firm in its faith in the imperishability of its sacred land, and mindful of its heavy burden of responsibility, and of the long road before it.” Mishima, devastated by the broadcast, vows there and then to use his literary skills to preserve and rebuild Japanese culture in the aftermath of the war. He records in his diary: “Only by preserving Japanese irrationality will we be able contribute to world culture one hundred years from now.”

November 25, 1970. For the last 25 years, Yukio Mishima has been a one-man literary institution, churning out some 40 novels, 50 theatrical pieces (including noh and kabuki plays), 25 short story collections, 35 more essay collections, a libretto, and a screenplay. He has delved into the demimonde, but also insinuated himself into high society. He has starred in movies, including Yasuzō Masumura’s 1960 yakuza film Afraid to Die, and has been featured as a photo model in Eikoh Hosoe’s Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses and Tamotsu Yatō’s Young Samurai: Bodybuilders of Japan.

Once a sickly child, he has embraced the aesthetic of taiyou to tetsu, of “sun and steel,” becoming a kendo master of the fifth rank, a battōjutsu practitioner of the second rank, and a karate martial artist of the first rank. He has conducted the Yomiuri Nippon Symphony Orchestra and joined the Nihon soratobu enban kenkyukai, or the Japan Flying Saucer Research Association. Few have embodied the maxim homo sum; humani nil a me alienum puto better than Mishima. But all these accomplishments will pale in comparison to what comes next.

As he listened to the emperor’s voice back in 1945, Mishima intuitively grasped that the post-war reconstruction of Japan would lead to a loss of kokutai, of “national essence,” and the replacement of Yamato-damashii, the “Japanese spirit,” with transplanted, invasive Western materialism. “Japan has lost its spiritual tradition, and instead has become infested with materialism,” he wrote in a September 3, 1970 diary entry. “Japan is under the curse of a green snake now. The green snake is biting Japan’s chest. There is no way to escape this curse.”

Horrified by the imperial rescript issued by Emperor Hirohito on January 1, 1946, which denied the divinity of the emperor, and by Japan’s 1947 Constitution, which he considered to be a “constitution of defeat,” Mishima formed a private militia called the Tatenokai, or Shield Society, the aim of which was to preserve Japanese culture and uphold the dignity of the imperial house.

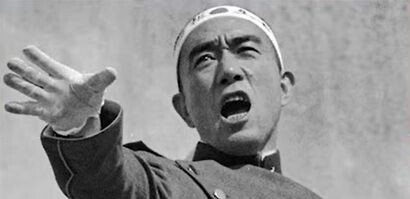

A fascinating, bizarre spectacle now unfolds before us. Mishima, alongside four other Tatenokai members, stormed the headquarters of the Eastern Command of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces, located at Camp Ichigaya in central Tokyo. Taking the commandant captive, Mishima orders the camp’s soldiers to gather beneath a balcony, where he informs them of the incipient coup d’état meant to restore the direct rule of Emperor Hirohito. The soldiers gathered below are no more interested in this outcome than the emperor himself, who naturally was never consulted by the Shield Society, and they begin to heckle Mishima, who is left wondering aloud: “Where has the spirit of the samurai gone?”

He hastily finishes his speech, cries out Tenno-heika banzai three times, and goes back inside to commit seppuku. Slicing open his abdomen with a short sword, he reaches for a nearby writing brush in order to write the Japanese character for “sword” in his own blood, but the pain is too intense. His fellow Shield Society zealot, Masakatsu Morita, nervously tries to behead his master but fails repeatedly, requiring another comrade, Hiroyasu Koga, to finish the job. Thus ends the Mishima jiken, the “Mishima Incident,” and with it, the life of one of Japan’s greatest writers of the 20th or any other century.

November 26, 1970. Mishima had requested in his last will and testament that he be cremated while dressed in the uniform of the Shield Society, a sword placed across his chest. His wishes are honored, but before he is reduced to ashes, his wife Yōko places a bundle of manuscript paper and his trusty fountain pen in the coffin. The next day, Mishima’s house is opened to mourners. One of the guests brings a bouquet of white roses, only to be gently chided by the deceased writer’s mother, Shizue Hiraoka: “You should have brought red roses for a celebration. This was the first time in his life that Kimitake did something he always wanted to do. Be happy for him.”

***

Yukio Mishima conceived of his life as a Gesamtkunstwerk, an all-encompassing work of art, and it is impossible not to view his life and his writing through the lens of his final act at Camp Ichigaya. He had been preoccupied with death from a young age, and his writing was suffused with, as Andrew Rankin, author of Mishima, Aesthetic Terrorist: An Intellectual Portrait, has put it, “obsessive assertions of the unity of beauty, eroticism and death.” He was fascinated by failed putschists, kamikaze pilots, and figures like Hayashi Yōken, the troubled Buddhist acolyte who burned down the Kinkaku-ji temple in Kyoto, inspiring arguably Mishima’s greatest novel, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (1956).

He read and re-read Yamamoto Tsunetomo’s Hagakure Kikigaki, an 18th century treatise on bushidō, the warrior code of the samurai, which beseeches the reader that “ when one has to choose between life and death, one just quickly chooses the side of death.” Mishima knew how his story would end, but he wanted to make sure that it was the story not of an “illegitimate child of modernity,” but of a “legitimate heir of history.” It seems fair to say that he succeeded.

Timed in conjunction with the hundredth anniversary of Mishima’s birth, the translator and academic Stephen Dodd has edited a collection of 14 short stories penned in the decade leading up to the Mishima Incident, Voices of the Fallen Heroes and Other Stories, all of which are presented in English for the first time. The stories reflect Mishima’s incredible range — we encounter the eery decadence of “The Strange Tale of the Shimmering Moon Villa,” the gritty realism of “Cars” and “Moon,” the apocalyptic horror of “The Flower Hat,” the existential mystery of “The Peacocks,” the supernatural elements in “Companions.” But it is in the title story, “Voices of the Fallen Heroes,” that we find Mishima at his very best.

“Eirei no koe,” or “Voices of the Fallen Heroes” — 英霊の声 could also be translated as “The Voice of the Heroic Spirits” — was published in June of 1966, and tells the story of a ritual of divine possession, a yūsai or séance, in which the disembodied voices of fallen soldiers of eras past are channeled through a 23 year-old blind youth. The soldiers come in two waves: the first comprised of young officers executed in the aftermath of a failed February 26, 1936 coup attempt, the second made up of the kamikaze pilots who vainly endeavored to turn the tide of the war in the Pacific. Their “chorus, interwoven with the sound of the flute, continued, now growing louder, now softer, like the distant sound of waves,” as the fallen heroes lament how

A twice-withered beauty dominates the world.

A mean-spirited truth alone is hailed as true.

Cars multiply, and foolish speed rends the human spirit.

Great buildings rise, but Righteousness collapses…

Emotions are dulled, and sharp angles worn smooth.

A passionate and heroic spirit has vanished.

Through the medium of the blind youth, “sometimes thousands, or tens of thousands, or hundreds of thousands of warrior spirits appear, joining their voices in satiric song that rebukes the vileness of the present age.” Mishima was likely experiencing something like survivor’s guilt, knowing that the unit he was meant to join upon completion of his army medical exam was completely wiped out in battle in the Philippines and that he never managed to join a kamikaze special attack unit before the end of the conflict.

For Mishima, the ultranationalist officers that died during, or were executed after, the February 26, 1936 coup were moral paragons in whose footsteps he sought to follow. Had their Imperial Way Faction triumphed, the nation would (at least Mishima argued) have been purged of corrupt politicians and rapacious zaibatsu capitalists, and Japanese foreign policy would have been based on the Hokushin-ron (“Northern Road”) strategy of confronting communism and driving into the northern Asian mainland, instead of the catastrophic Nanshin-ron (“Southern Road”) strategy of expansion into Southeast Asia and the Pacific islands, which led to a confrontation with the Allies and the total destruction of the Japanese empire.

When their coup failed, “the dominant military faction, quasi-Nazis filled with malice, opened up the road to war, without obstacles of any kind.” Later, the kamikaze pilots who turned themselves “into living bullets and targeted the enemy ships, for the sake of our emperor who was a god,” would likewise be betrayed, this time by the imperial rescript that stated once and for all that the emperor was not a god, and that the Japanese state was no longer to be “predicated on the false conception that the Emperor is divine.”

This, to Mishima, was the ultimate breach of faith. “We can accept Japan’s defeat,” the ghosts declare. “We can accept the land reforms,” “we can accept socialist reforms,” “we could accept humiliation,” but “Why did our divine sovereign lord become no more than a human?” They ask this over and over again, and as the “angry divine spirits had reascended at last,” the séance-goers discover to their horror that the blind youth has perished, his face in death no longer his own, transformed “into the ambiguous face of someone unknown.” Mishima himself had given voice to the thousands of martyrs to the imperial cause. One day, he would join them.

***

No writer, in Japan or elsewhere, has better described the consequences of what John Nathan has called the “agony of cultural disinheritance” better than Yukio Mishima. At the time of his coup attempt, Japan was beginning to reap the benefits of the Yoshida Doctrine, devised by the postwar Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru to ensure economic growth through international trade, international security through an alliance with the United States, and international repose through the strict limiting of Japan’s Self-Defense Force. The benefits were enormous — Japan was the second-largest economy in the world between 1968 to 2010 — but it did not leave Japan’s “national essence” or “spirit” untouched, just as Mishima had warned.

Christopher Harding, writing for Engelsberg Ideas, has observed that Mishima’s conception of a spiritually revitalized Japan remains relevant, particularly in these geopolitically parlous times:

Though Mishima was partially eclipsed in later years by authors like Haruki Murakami, particularly outside Japan, in his centenary year he speaks to a basic unease that many Japanese would still recognize. Japanese leaders are struggling to stabilize the economy and to give an account of what their country stands for beyond the peace and prosperity that was once taken for granted but which is now threatened by China’s rise and Japan’s rapidly ageing and shrinking population. Mishima’s dream of a nation imbued with purpose and passion, seeded by childhood trips to watch kabuki plays with his grandmother, feels as compelling — and perhaps as disturbing — as ever.

Mishima, in his 1945 diary entry, pledged to preserve “Japanese irrationality.” For him, the kamikaze pilots of the Second World War embodied this irrationality. By becoming the Divine Wind, a kamikaze pilot, as Mishima wrote in “Voices of the Fallen Heroes,” became himself “a mystery. To cause us human beings to pray to something within ourselves, to have faith in something within ourselves. Our deaths embodied that. But if we ourselves are a mystery, if we are living gods, then His Majesty above all must be a God. He must deign to shine as a god on the highest step of divinity. For that is the foundation of our immortality, of the glory of our deaths; that is the only thread tying us to history.”

Without that sense of the divine, then “our deaths would become nothing more than a foolish sacrifice. We would not be warriors but gladiators in the arena. Ours would not be the death of a god but that of a slave.”

Mishima’s “fallen heroes” may be particularly extreme examples, but as we have seen, Mishima was attracted to extreme cases, being one himself. This does not make it any less true that, as Nietzsche so famously argued, the “meaninglessness of suffering, not the suffering, was the curse that lay over mankind so far.” Mishima understood that people need meaning, they need roots, and mystery, and a collectively-shared national essence in order to thrive spiritually and culturally.

It is a lesson that holds good today. A century after he was born and 55 years after he met his heroic, foolhardy, irrational, and grisly end, we still find Mishima’s works compelling and disturbing in equal measure. Perhaps it would be fitting to end with an adage from one of his favorite sources of wisdom, the Hagakure Kikigaki, which assures us that “even after one’s head has been cut off, one can still perform some function,” which has certainly proven the case when it comes to the inextinguishable legacy of Yukio Mishima.

READ MORE from Matthew Omolesky:

The Obligations of Home: JD Vance and the Ordo Amoris

Bauhaus and the Cult of Ugliness

Never Had It So Bad: The Decline of the Great British Empire

![Trump's Admin Guts Another ‘Rogue Government Agency with Zero Accountability’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Trumps-Admin-Guts-Another-‘Rogue-Government-Agency-with-Zero-Accountability-350x250.jpg)

![‘We All Owe Him (Elon) a Huge Debt of Gratitude’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/‘We-All-Owe-Him-Elon-a-Huge-Debt-of-Gratitude-350x250.jpg)

![NCAA Champ Salutes President Trump After ‘BIGGEST UPSET IN COLLEGE WRESTLING HISTORY’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/NCAA-Champ-Salutes-President-Trump-After-‘BIGGEST-UPSET-IN-COLLEGE-350x250.jpg)