My mother died last week at the age of 92. For the rest of my life, every Ash Wednesday will evoke her memory. Not that I’ll need a Holy Day of Obligation to always remember her. She was not only my beloved mother, but one of the last representatives of a bygone civilization where grace, sophistication, and elegance reigned supreme. Mom radiated these virtues to everyone around her, and they admired her for it.

I drove her to her treatments every day, and we bonded in a way we never had before, which I’ll always cherish.

Vera Mestre was Cuban aristocracy when the island was still a Spanish-cultured state, even though her grandfather fought the Spaniards beside Jose Marti in the Second Cuban War of Independence. Like many former European colonies other than the United States, a feudalistic system endured there. But the sense of gusto in the Cuban people superseded most class resentment — until a Marxist devil invoked it for power and doomed them.

Pre-Castro, mom was upper class in a family of industrious men. Her father, Luis Augusto Mestre, and his two brothers, Goar and Abel, dominated Cuban commerce. They ran a pharmaceutical empire that started in the 1840s. Goar was the visionary, always looking for the next advantage, Luis Augusto the workhorse, and Yale-educated Abel the face of the business.

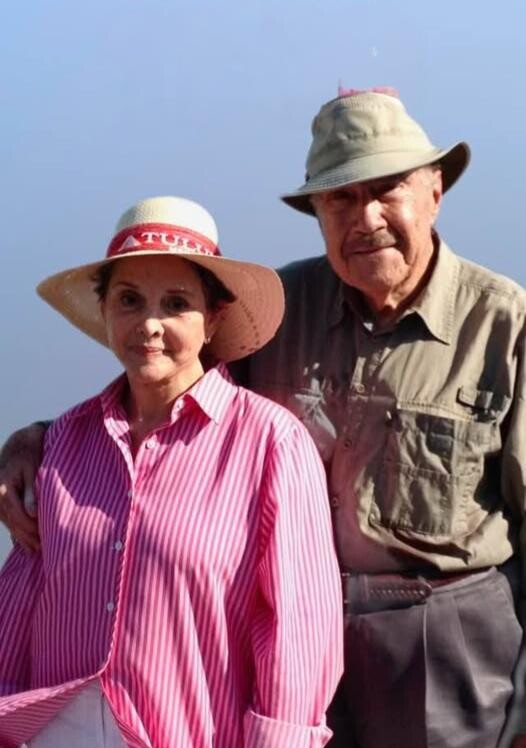

The author’s mother Vera and husband Juan Grau (Lou Aguilar for The American Spectator)

During World War II, Uncle Goar grasped the commercial value of radio in Cuba. He acquired a 50 percent stake in station CMQ (Cuba Me Quiere – Cuba loves me) from its founders, Miguel Gabriel and Angel Cambó, turning it into the Cuban superstation. Goar soon saw the wealth potential in television. In 1950, he made a deal with NBC in America to launch CMQ-TV, which helped make Cuba the first Latin American country with the exploding medium. This further enriched the Mestre brothers, just before their world ended.

I remember Luis Augusto’s wife, my grandmother Carmen, as a Dickensian grande dame a la Miss Havisham. Mom inherited her mother’s haughtiness minus the hardness. She resented — always in private — when the workers in her Key Biscayne condo building addressed her by her first name instead of Señora Vera, to the amusement of my brother and me.

Mom had been loved by two extraordinary men. The first was my father, Luis Aguilar Leon. I wrote about him in an article here. How he originally championed his old school chum Fidel Castro, then opposed him when he shut down the free press, which put his name on the firing squad list. He continued to be a thorn in Castro’s side for 30 years as an eminent Georgetown University professor and author.

When dad got sick, I moved to Miami from LA to help look after him. It was no great sacrifice, as my criticism of Barack Obama had made me persona non grata in Hollywood. But I’ll never forget the night I took mom out for a rare restaurant supper. When we came back to dad’s sickbed, mom took hold of his hand. Dad coughed once and died. He’d waited for mom to come home before moving on to his rest.

I remained in Miami to write, returning to my first love, books, after a decade of screenplays. So, I was there when an old friend and neighbor of mom from Santiago, Cuba began courting her. Juan Grau was the opposite of dad, not an intellectual but the archetypal macho Cuban — a sportsman, former big game hunter, and tycoon, now widower.

Juan had run the singular Cuban liquor giant Bacardi in Mexico, and he would treat mom in the high style she’d grown up in, with restaurants, shows, and cruises. One day during the courtship, mom asked me if I’d approve of her dating Juan. I said, “Mom, you’re 84. Go wild.”

She and Juan had seven wonderful years together before COVID and a broken hip brought him down. Soon afterward, mom got breast cancer. I drove her to her treatments every day, and we bonded in a way we never had before, which I’ll always cherish. She overcame the cancer but never physically recovered. Though she continued to play canasta with her dear great friends, whom she affectionately called la pila de viudas (the pile of widows), as they had all outlived their men.

Remaining mostly in her room, mom looked forward to my nightly visits to watch Laura Ingraham, a TCM-recorded movie of my selection — “Nada que me de anxiedad,” she insisted (“Nothing that will make me anxious.”) — then an episode of Perry Mason. She liked that I was best friends with Della Street’s – actress Barbara Hale’s – son William Katt (The Greatest American Hero), who later played Paul Drake Jr. in the Perry Mason movies. We got through eight seasons of the series and four episodes of the final season before mom had to go to the hospital with breathing problems. I wish we could have watched the last 26 episodes.

The desk clerk of my mom’s apartment building is a Cuban exile named Reynaldo. He’s been on the job since 1992 and seen it all: Residents strut in like winners and be carried out on stretchers. My dad healthy then lost to dementia. Juan and mom dressed to the nines then Juan unable to walk. And mom go from high heels to a wheelchair pushed by me. Reynaldo always called her Señora Vera. The morning after she died, he saw me and burst into tears. “Your mother,” he cried, “was a great lady.” In her case, truer words were never spoken.

As a codicil to mom’s story, I met Angel Cambo’s grandnephew Manuel Cambo in Key Biscayne, where we both live. Manny owns and operates a radio station, WSQF, on the island like his grand uncle did in Cuba. For two years, he and I have been doing a political talk show. Mom loved the thought of a Cambo and a Mestre (me) together again on radio.

We asked her to come on the show and talk about her Cuba years. She intended to when she got better. But on Ash Wednesday, she kept another date — with Our Lord. I hope one day He’ll extend the same invitation to me, so I can see mom again. To quote a line from my favorite book, The Three Musketeers, “She was an angel on Earth before becoming one in Heaven.”

READ MORE from Lou Aguilar:

![Trump's Admin Guts Another ‘Rogue Government Agency with Zero Accountability’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/Trumps-Admin-Guts-Another-‘Rogue-Government-Agency-with-Zero-Accountability-350x250.jpg)

![‘We All Owe Him (Elon) a Huge Debt of Gratitude’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/‘We-All-Owe-Him-Elon-a-Huge-Debt-of-Gratitude-350x250.jpg)

![NCAA Champ Salutes President Trump After ‘BIGGEST UPSET IN COLLEGE WRESTLING HISTORY’ [WATCH]](https://www.right2024.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/NCAA-Champ-Salutes-President-Trump-After-‘BIGGEST-UPSET-IN-COLLEGE-350x250.jpg)